This is a special edition of the Media Matters blog. True to the mission of this blog, this post is about media; about a documentary film project and about sensational and scurrilous media that contributed to a literal conflagration fueled by racial hatred. But is is also about much more than that.

In recent months I have been researching and writing a script for a historical documentary about the Great Flood that struck the city of Pueblo on June 3 of 1921. The program is finished and the episode of Colorado Experience will air on RMPBS this Thursday evening; 100 years, to the day and nearly to the hour, after that tragic event.

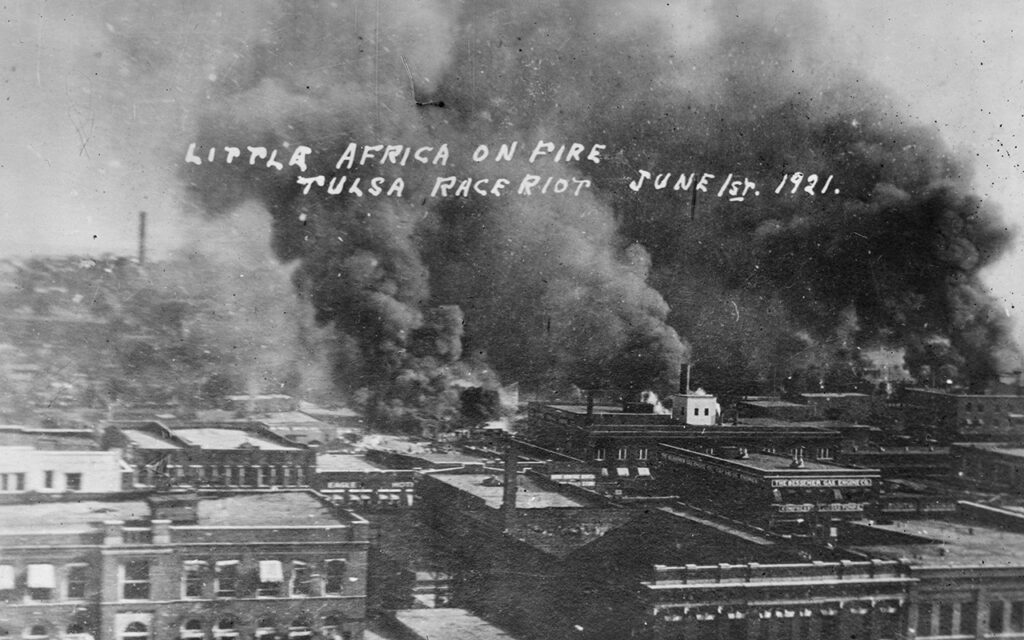

But in researching the Pueblo flood I also learned about a tragedy that happened 72 hours earlier in a city 600 miles downstream of Pueblo, also on the Arkansas River. Tulsa, Oklahoma was the site of perhaps the worst incident of racial violence in the history of the United States. And despite efforts to sweep it under the rug, the reality of that injustice is slowly coming to light. Oklahoma finally commissioned a study of the 1921 event in 2001; 80 years after the fact. Recent focus on racial justice (and injustice) is shining a new light on the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921 and previously hidden stories of horrific deeds are finally coming to light. In fact Tulsa is the scene for the HBO’s Watchmen series, giving the historic narrative a superhero treatment and much greater exposure than any textbook or documentary. You can also read more about Tulsa in this “graphic novel” sponsored content at The Atlantic magazine.

It is important to view historical events through the lens of the cultural and ethical norms of the time. While not an excuse for racial bigotry and oppression, it is important to understand that norms have changed substantially in the past 100 years. And of course one of the clearest markers of how far we’ve come is to compare the mass media then and now.

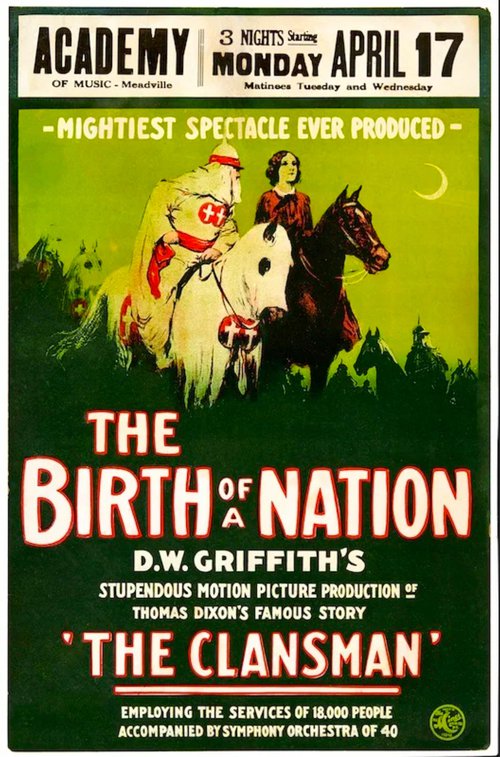

Mass media in various forms contributed to the cultural climate in the late 1910’s and early ’20s and, in some cases, contributed directly to the actions that followed. The Birth of a Nation, by D. W. Griffin, was a major cinematic accomplishment and blockbuster when it was released in 1915. At the same time it was a viciously racist film that led to demonstrations and condemnation.

The film was hailed by critics and was given a private screening by President Woodrow Wilson in the Whitehouse. President Wilson remarked about the film, “It’s like writing history with lightning. My only regret is that it is all so terribly true.” But like the destructive and deadly nature of lightening, the film not only captured the racists sentiment of the time, it likely contributed to the Red Summer and growing racial unrest of the late 1910s.

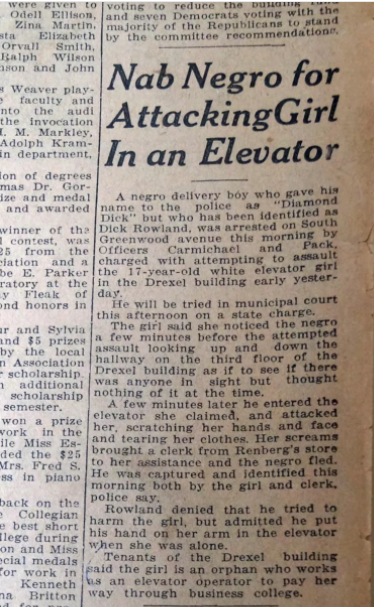

Another example of the media’s role in setting the stage for Tulsa’s tragedy is more direct. The day after the alleged assault by a black teenager boy on a white teenage girl, the local newspaper, the Tulsa Tribune, ran a short article on the front page calling for action. At this time in this part of the country this was clearly a call for vigilante justice in the form of a lynching.

To be fair, Pueblo was also familiar with lynchings. Just two years earlier two Mexican men accused of murder were busted out of jail and hung from the 4th Street bridge over the Arkansas River.

The idea of vigilante justice may seem like something from our past, but recent apps like Citizen and Vigilante suggest that there will always be a market for incitement to direct action outside the bounds of the criminal justice system.

Allow me to first draw a few parallels between the events 100 years ago in Tulsa and Pueblo, and then we’ll turn our attention to the differences. As mentioned, both cites were built on the banks of the Arkansas River. Similar in size, the racial/ethnic makeup of the two cities was quite different. Tulsa was majority white, but with a large Black population. Pueblo was a melting pot of ethnicities with a small Black population. Pueblo was ethnically diverse because of immigrants from Old and New Mexico, southern and eastern Europe, and literally dozens of other countries. In fact the CF&I steel mill recorded more than 40 languages spoken by its employees, and the town of Pueblo had about 24 foreign-language newspapers at the beginning of the 20th century.

After the Race Massacre in Tulsa and the Great Flood in Pueblo, victims were likely buried in mass graves. In Tulsa the mayor has requested a study to determine if a mass grave exists and if it contains the bodies of murder victims. In Pueblo, recent studies using ground-penetrating radar have given researchers reason to believe that a mass grave at Roselawn Cemetery on the southeast side of town may hold victims of the flood.

Lucille Corsentino, of Roselawn Cemetery in Pueblo, explains how research by Colorado School of Mines and Alpine Archeological Consulatants is attempting to discover if a mass burial site may contain victims from the Great Flood, as well as others who died in tragic events in preceding years.

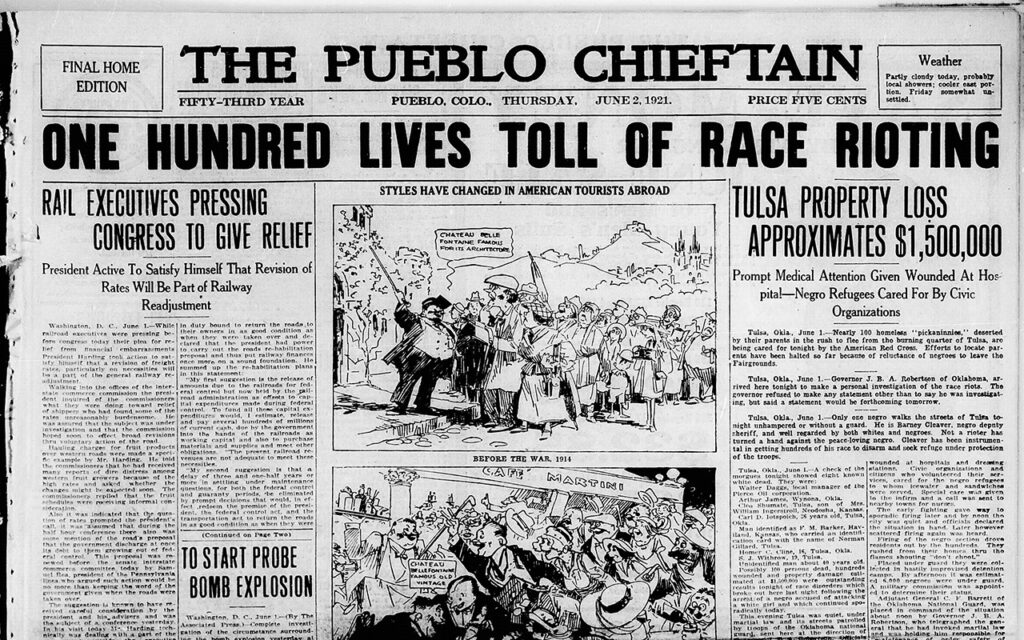

The official count of victims from the massacre and the flood is similar, with estimates in the low hundreds. However, both events have led to serious questions about under-counting of victims and estimates of the true number of deceased vary widely. In both Tulsa and Pueblo we’ll never know with certainty how many lives were lost.

Estimates of damage to buildings and infrastructure were more accurately assessed. In Pueblo the estimate is in the neighborhood of $200 million, with Tulsa not far behind. Pueblo saw the destruction of more than 600 homes and businesses, and the fires in Tulsa destroyed 35 city blocks and more than a thousand homes leaving many homeless.

In both cities martial law was declared and National Guard troops were called in. Also, in both cities able-bodied men were forced to work on clean-up efforts under threat of jail time.

The day before the flood struck Pueblo, the headline in the Pueblo Chieftain newspaper announced the death and destruction in Tulsa.

While the Tulsa Race Massacre was largely white on Black violence in the segregated neighborhood known as the Greenwood District, also known as Black Wallstreet, the Pueblo flood was indiscriminate in the way that it destroyed property and took lives. While Pueblo’s wealthier residents lived on higher ground further from the rivers, many of their businesses in the downtown area were heavily damaged. Immigrants and the poor who lived in the flood plain were subject to great loss as the roaring water washed away everything that stood in its path.

Colette Carter, professor of Political Science at CSU Pueblo, spoke with me about the nature of our response to a man-made disaster (Tulsa) versus a natural disaster (Pueblo).

A question raised by Dr. Carter remains unanswered. How long will we continue to ignore the painful episodes of our history, and can we ever move forward without a serious reckoning as a nation? According to the 2001 Tulsa Race Riot report, “Not one of these criminal acts was then or ever has been prosecuted or punished by government at any level, municipal, county, state, or federal.”

On some spiritual dimension I can’t help but wonder if the flood in Pueblo wasn’t caused by a deluge of tears over the injustice that had taken place in Tulsa just 72 hours earlier.