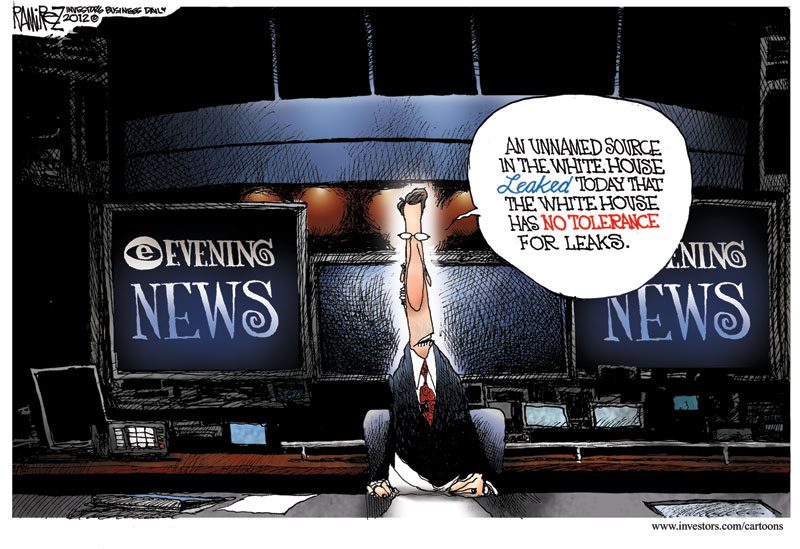

Recent concerns about government prosecution of “leakers” and journalists has reignited a conversation about the limits of 1st Amendment protection for journalists and sources. Journalists sometimes become recipients of very sensitive information that may have implications for national security. At the same time they feel an obligation to protect the identity of whistle-blowers to ensure the free flow of important information. Some are calling for a federal “shield law” that will provide additional protection for sources, and for the journalists who report on the information they provide.

Recent concerns about government prosecution of “leakers” and journalists has reignited a conversation about the limits of 1st Amendment protection for journalists and sources. Journalists sometimes become recipients of very sensitive information that may have implications for national security. At the same time they feel an obligation to protect the identity of whistle-blowers to ensure the free flow of important information. Some are calling for a federal “shield law” that will provide additional protection for sources, and for the journalists who report on the information they provide.

This dilemma involves very difficult situations where the intersection of national security concerns and “the public’s right to know” appear to be in conflict. Recent news out of Washington has been focused on the government going after the phone records of AP reporters and investigating Fox News reporter James Rosen. Many have viewed these actions as prosecution of the act of journalism which will have a chilling effect on future whistle blowers and other sources. While it can be argued that much of this hand-wringing is really politically motivated, there are plenty of examples of attempts to control information by both Republican and Democratic administrations.

In February of 2013 Pvt. Bradley Manning plead guilty to 10 of 22 charges for his part in the release of what has been called the “biggest leak of classified material in U.S. history.” Manning uploaded the classified documents from the Iraq war to Wikileaks after failing to get a response from the New York Times or the Washington Post. (See earlier blog post on Manning and Wikileaks)

What Wikileaks founder Julian Assange had attempted to do as a “radical transparency activist” is now going mainstream with the release of Strongbox. The New Yorker magazine has launched Strongbox as a way to provide a greater level of security and anonymity to sources who may fear reprisal if their identity were to be revealed. According to the Strongbox website,

Strongbox is designed to be accessed only through a “hidden service” on the Tor anonymity network, which is set up to conceal both your online and physical location from us and to offer full end-to-end encryption for your communications with us. This provides a higher level of security and anonymity in your communication with us than afforded by standard e-mail or unencrypted Web forms.

At least one problem remains. Typically a journalist needs to independently verify the veracity of information received from a source, and this level of anonymity may make that difficult if not impossible. But it is one more tool in the arsenal of investigative journalists who are committed to rooting out corruption and wrong-doing at the highest levels of government and industry.

Video resources:

It seems that investigative journalists have two risky choices when it comes to their sources. Staying in contact with a source can be hazardous as “the U.S. Supreme Court decided that the First Amendment offers reporters no protection from grand jury subpoenas” (Turow 101). On the other hand, failed use of the plausible deniability that comes with Strongbox has the potential to ruin a reporter’s credibility which could mean a destroyed career. With no real way to verify the legitimacy of every component in a range of tips to major leaks, reporters may have to decide whether or not an unverifiable story is worth risking his or her career. On an even larger scale, reporters have to choose between that and potential jail time. Not taking these risks, however could be even riskier. According to Justice Hugo Black, “Only a free and unrestrained press can effectively expose deception in government” (Turow 82). Investigative reporters have a tremendous amount of power and the consequences can be extremely positive or cripplingly negative.

Works Cited

Turow, Joseph. Media Today: An Introduction to Mass Communication. 4th ed. New York: Routledge, 2011. Print.